If you are fortunate enough to find yourself stuck in traffic with Gordon Huether, your very perception of time and space may just be altered. “Everyone has sat in bumper-to-bumper traffic,” the sculptor says by way of explaining his fascination with nature’s effect on man-made objects. “Maybe at some point you’re behind a beat-up old truck. And maybe it has stains and rust patterns on it.” Or take for example the weeds pushing up a poured sidewalk, he continues, or bird droppings splattered along an exterior wall. “Humanity is so preoccupied with making things, manipulating things,” he says. “But nature has a way of taking things back.”

It’s a curious perspective from one who creates large-scale installations that define the entrances of corporate headquarters or suspend playfully overhead in cavernous airport terminals. The artist may have made a career of beautifying architectural spaces with his ambitious glass designs that incorporate a variety of materials and found objects, but their temporal quality is not lost on him.

In fact, through his art Huether strives to prompt passers-by to stop and recall the larger forces of nature and time at play in even the most mundane of moments. “So instead of sitting in traffic and just looking at this beat-up pickup truck,” he concludes, “maybe you can also see some beauty in it.”

The Timeless in the Temporal

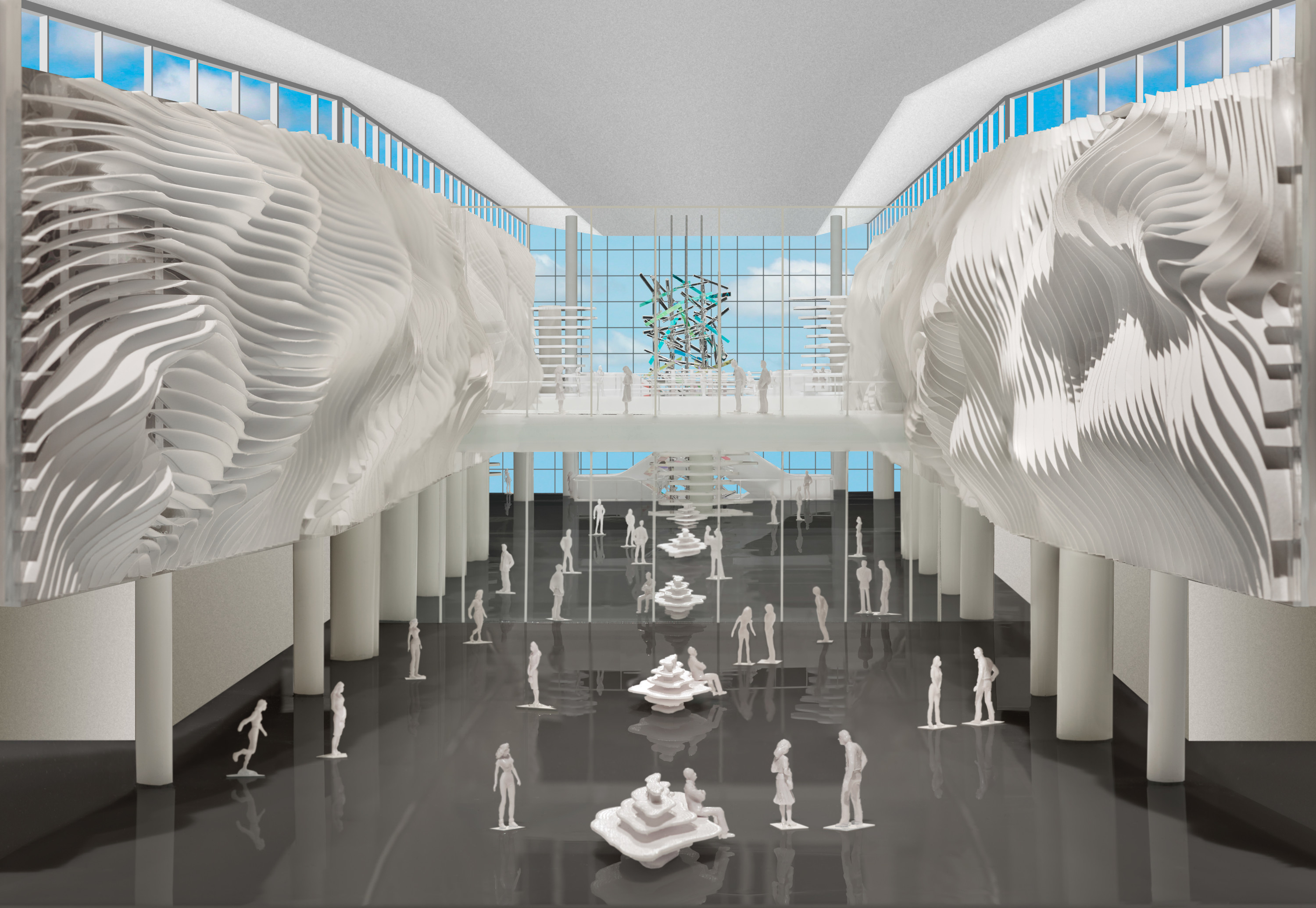

For Huether’s most epic depiction of this vision, a visit to the Salt Lake City International Airport is in order; that is, not until 2020, which is the anticipated year of installation for the artwork. Inspired by the region’s striated sandstone formations, Huether enveloped the three-story main concourse—spanning the length of a football field—with seven miles of aluminum tubing and some two acres of composite fabric. Entitled the “The Canyon,” his installation lines the walls with three-dimensional tensile fins that run in undulating parallel lines, evoking the circuitous walls of the canyons that inspired them.

“What’s so interesting to me is that those striations and curvatures took millions of years to form,” Huether says. “It changes your whole perspective of time and space.” Throughout the airport, his additional installations encase a central escalator with multicolored light-reflecting glass rods and provide weary travelers with functional seating and visual cues.

The massive scale of the project, paired with the nearly timeless formations they evoke, lend drama to an already dramatic space. Huether says his designs serve to “humanize” such vast and utilitarian spaces. To that end, he designed each installation with the relentless throng of bustling and preoccupied passengers in mind.

“I travel all the time and I know that stress,” Huether says. “Even as a seasoned traveler, there’s still the parking, the elevators, security, boarding passes…” In the face of such a taxing experience, Huether thought, “how cool would it be if you stepped into this space and it inspired you and took your breath away or even shifted your experience of time?”

From Order Comes Inspiration

One of the best means of gaining insight into Huether’s approach is to understand the forces of time and space that shaped the artist himself. A child of German emigrants who met on a boat headed for the United States, Huether’s early years were characterized by his father’s methodical stoicism set against the backdrop of the community they found themselves in—the unstructured experimentalism of 1970s California.

“My father believed that the world had been in cultural decline since the Renaissance,” Huether remembers. “So I grew up with rare books, German philosophers, classical painting, all that kind of stuff.” Yet Huether’s father was also the person who—after seeing the extent of his teenage son’s rebellious frustration—introduced him to his first artistic medium. The stained-glass pattern and box of colored glass that appeared on the kitchen table one day launched his glass-designing career. “He could see I was desperate to find my way in life,” Huether says, “and he pushed me in that direction.”

Photo by Partners 2 Media

True to the artist’s roots, that direction—while stirred by the “sensual, ethereal” qualities of glass—is in equal measures methodical and orderly in its implementation. Today, the comprehensive infrastructure of his Napa, California studio equips Huether and his team to execute every stage of a commissioned project on time, on spec and on budget. Not only does his insistence on efficiency “take some of the fear out of engaging with the artist,” he believes, it also allows him the ability to accommodate the unique constraints of a site or a client’s particular parameters.

In fact, says Huether, it is that long-familiar tension between structure and inspiration, the mundane and magical, that feeds his artistic process. “I have found that the more restrictions, the more challenges on a project, the more you find yourself going to corners of your creative spirit.”

Humanizing the Mundane

To that end, Huether’s treatment for a parking garage in Morgan Hill, California might just be his ideal project. “It doesn’t get more mundane that a parking garage,” he laughs “But that’s the challenge I enjoy.”

Leading a team of architects on a successful bid for the project, Huether proposed enormous transparent glass panels to enclose the three-story stairwell in vibrant oranges, reds and yellows. At night, the panels glow in a pattern inspired by a microscopic image of Poppy Jasper, a mineral native to the region. On the building’s opposite side, a bejeweled tarantula, its body 12-feet in diameter and composed of hundreds of vintage automobile headlights, scales the structure’s wall. It’s a playful nod to the community’s migrating arachnid population, celebrated at the town’s annual festival.

“I love that it creates this very dramatic lantern that basically takes a utilitarian building and makes it into something more exciting, even beautiful,” Huether says of the Poppy Jasper project. Even better, he says, the installations reflect the community’s unique qualities and identity. “I realized many, many years ago that art is not about me but about the people that use the building every day,” Huether says. “Everything I do wants to tell a story. And it’s almost always someone else’s story.”