Using data—and being used by it—has become a pervasive and essential part of our daily lives and the accepted way the world works, yet it’s largely invisible. When phenomena become so widespread and embedded in culture that they fall into the background of our everyday assumptions, times are often ripe for artists to step in and give us new, coherent expressions of their meaning.

Artist Jonathan Spring has built a career doing just that, producing a body of innovative three-dimensional work he calls “Datascapes.”

“We are surrounded by data,” Spring explains, “and some by itself is quite beautiful. Yet there is so much more to the world of data than its mere depiction. It’s like the difference between looking at Monet’s garden and looking at Monet’s paintings of his garden. Data has transcendent emotional, societal, and aesthetic qualities that I try to capture in my work; in that way, others can enjoy those meanings, too.”

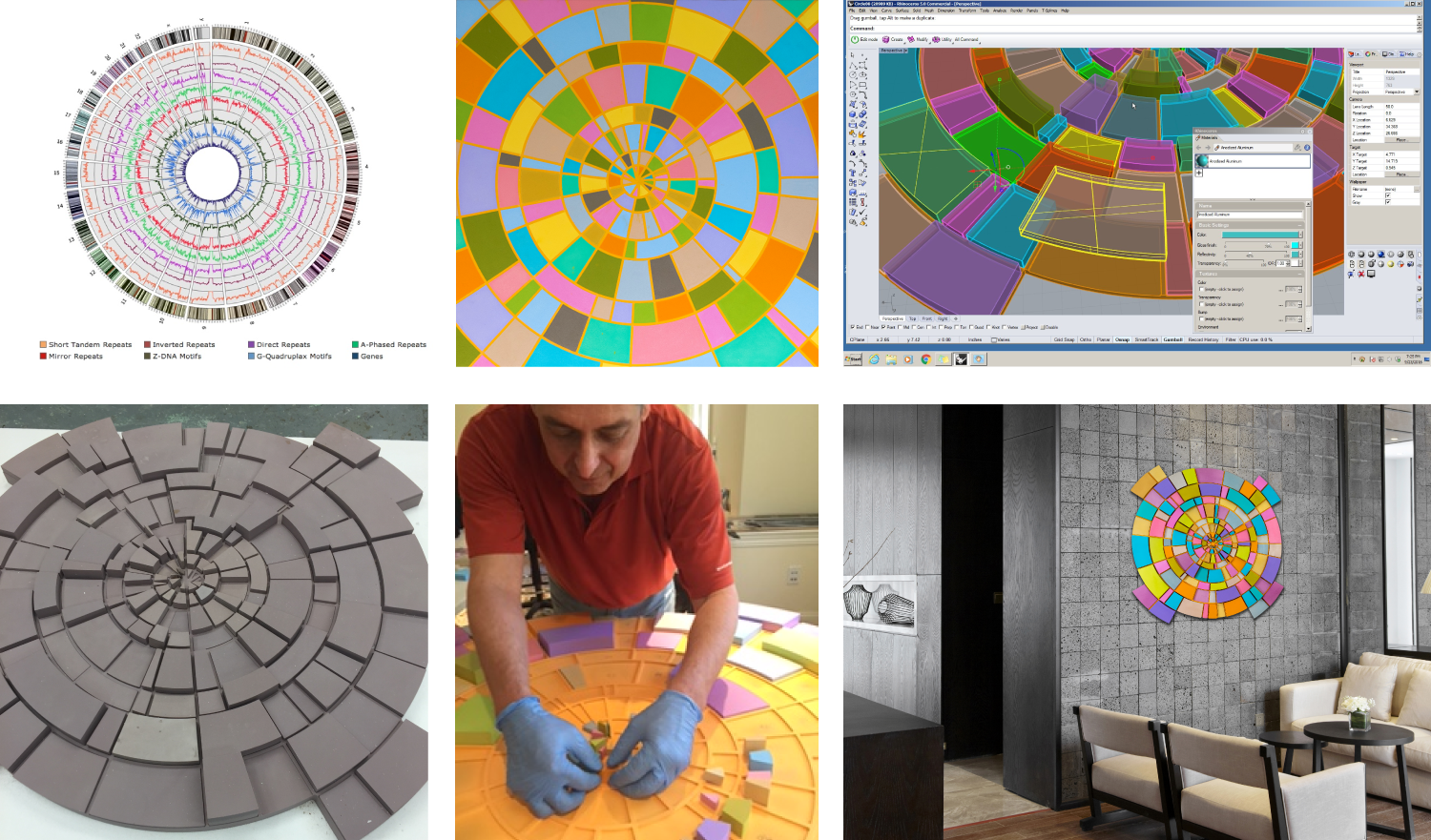

Spring seems to have hit a deep chord with both technology-based organizations and distinguished collectors. In his Datascape, Why Me?, for example, Spring made a deep study of actual DNA data to create a bright, undulating wall sculpture. Weaving together genotype structures that help determine inheritable traits with the purpose of discovering such links, Spring ultimately created a piece that feels precise and scientific, yet pulses with color and movement suggesting the energy of existence.

Beginnings and Monet

The incorporation of data and technology comes naturally to Spring, who has spent a lifetime in careers driven by their exploration. An MIT undergraduate who went to school to become an engineer, he was drawn to the Institute’s graduate film program. In his sophomore year, Spring was hired to create a forward-thinking film about the increasing syntheses of art and technology at MIT. He would go on to a fifteen-year career making promotional films worldwide that melded art and technology.

His professional life took a turn in the mid-1990s when he met the first trader to bring a computer to the floor of the Chicago Board Options Exchange. They decided to work together, processing huge amounts of data to electronically price orders via computers in real time, and became one of the world’s earliest high-frequency trading firms. The business grew quickly and was sold three years later. Successful ventures with hedge funds and trading companies followed, all with an emphasis on trading using huge volumes of data and creating algorithms designed to increase speed and profitability.

But it was a vacation with his wife to Paris in 2007 that would remind Spring of what his data-driven life was missing. “I was hugely absorbed in the financial world and creatively feeling like a dried-out sponge,” Spring recalls. “And then one afternoon at the Musée de l’Orangerie, I had this overwhelming emotional response to Monet’s Water Lilies, and I realized that an edge of my sponge was being deeply replenished. At that moment, I committed myself to learning how artists use paint and other materials to provoke such deep human feelings.”

Spring had never painted or even learned basic drawing techniques. So he set out to teach himself, rigorously starting out in charcoal and pencil, moving to pastels, and finally, after five years, he began making oil paintings. He put years into understanding the technical aspects of art; for example, how Rothko brought old-master glazing techniques to twentieth-century abstract expressionism. He soon realized that art is about making deliberate choices among the techniques at your command, while not necessarily knowing in advance what the “right” choices are. Says Spring, “For many artists and viewers, the power of art is discovering what “right” choices can be.”

Data + Art

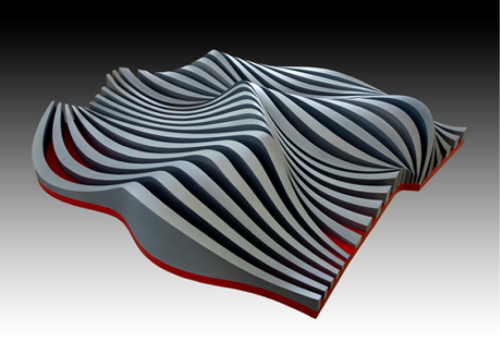

Still spending his days looking at data, Spring began to consider how to incorporate his views about information and technology into his art. Spring’s first Datascapes were highly praised oil paintings but, adds Spring, “I felt they were crying out for dimensionality.”

Achieving three-dimensionality in his work was a challenge that required techniques not often found in traditional artists’ studios. First, he had to teach himself CAD so he could translate his paintings into 3D works of art, and then embrace CNC milling for its precision and detail in bringing his visions to life. “It wasn’t easy, at first, to find a fabricator who would touch my projects,” Spring laughs. “They are using computers and machines that are typically aimed at producing complex prototype parts for airplanes and satellites, and I’m showing these fabricators my CAD files for artwork! They said I was out of my mind.”

Spring finally found an experienced industry partner in New Jersey’s Digital Atelier, which has fabricated sculpture for Jeff Koons, Kiki Smith, Tom Otterness, and dozens of other prominent artists. While Spring’s designs can be milled in metal or stone, he often turns to high-density resin for its light weight, archival quality, and ability to hold detail and color. Pieces are often finished in durable automotive paint, and he encourages viewers to touch his artwork if they feel the urge. “I make my pieces sturdy enough so people can add a tactile facet to their experience,” says Spring.

And no matter if a client asks Spring to work on a broadly conceptual or a highly specific notion of data or technology, or whether the final piece is to reflect a specific moment in a company’s history or requires broader artistic interpretation. “It’s my goal to emotionally translate data and technology in ways that are truly engaging, creating objects that have endurance and can be considered repeatedly from a multitude of perspectives. If you want to say something artistically about technology and data, I am a person to visit because I’m already there. That’s where I live.”