Don’t be surprised if you find Susan Wink hosting an open meeting or free workshop if she designs public art for your neighborhood. There’s also a chance you’ll be rifling through your old photos of the area or contributing your own design to a custom tile.

“Really, I believe everyone has artistic abilities,” says Wink, a sculptor and ceramicist with a background in art education. “I believe so strongly in that. Everybody can make a mark—you sign your name every day. So, you can get people to make a simple image, shape or texture—then afterward they are pleased with what they have done.”

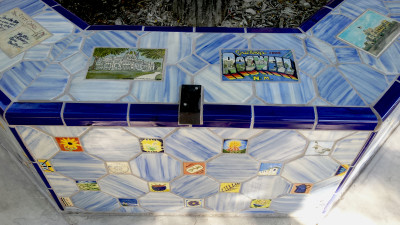

Photo credit – Susan Wink

It would be hard to imagine residents not pleased with the interactive public art projects Wink has created for and with them over the past two decades. After all, whether running a hand along a bridge’s decorative railing, following a trail of individually shaped stones or pausing on a custom-tiled park bench, the many elements that surround visitors are likely to reflect their own lives back at them.

“I really see it as a courtesy,” says Wink who is fascinated with people’s stories and passionate about designing spaces that connect to an area’s natural and cultural history. “How could I understand a community if I didn’t talk with people and find out the nuances and unique details of the place?”

Interactive Art Begins with Interactive Design

Take for example Wink’s railing design that adorns the Camino Alire Bridge in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “The neighbors were involved because their neighborhood is incredibly important to them,” she remembers. “The people I interviewed told me about the historic significance of agriculture along the river and about the distinctive cultural mix of that area.” In response, she based the railing’s motif on elements of the corn plant, commemorating the region’s Native American and Spanish settlers.

While designing the community -based project “Remembering Roswell,” one resident’s rich trove of old postcards inspired Wink to teach workshops to members of the local potter’s guild in so they could reproduce the images as tiles on the park’s custom concrete benches. In fact, each art feature Wink designed for the Main Street pocket-park renovation was intended to celebrate Roswell, New Mexico’s rich history and cultural vitality: photos from the historical society’s archives inspired the design of the entry column arches, the decorative hand-forged iron grille railings, and a large mural showcasing an antique postcard image of the city’s Main Street from 1900.

While Wink has frequently partnered with the same welder and drafting (CAD) designer, she seeks out talented local fabricators, electricians, masons and muralists. She also welcomes the opportunity to join forces with public art consultants and city planners and engineers. “It is a thrill to see a project installed,” Wink says of such a collective effort. “It’s the culmination of months and sometimes years of planning and work coming to fruition.”

Problem Solving Makes for Special Places

Undoubtedly, coordinating a community-wide project requires no small degree of leadership skills. “You do have to be strong in your vision,” Wink allows, “but not inflexible. When art is in the public realm it just comes with restrictions that require creative problem-solving solutions.”

Photo credit – A.T. Willet

In fact, some of her most gratifying commissions were born from influences that sent the project in an entirely new direction. When designing “Flight of Time,” for example, a Tucson, Arizona Modern Streetcar stop, Wink sat down with the owner of the Time Market Deli whose storefront sits across from the site. “He told me ‘I’d like to see something that has movement,’” she remembers. “That conversation sparked a new design direction I hadn’t considered.”

Over 2,800 “word” tiles were made by multi-generational Roswell residents in numerous free public workshops held throughout the city. Individuals made “word” tiles based on their favorite authors, poets, or words. The sculpture was a community effort with funding secured through grants and donations from community members and businesses. The sculpture was commissioned to celebrate the Roswell Public Library’s centennial.

Photo credit – Susan Wink

In the end, the piece became an experience of movement through time itself. Overhead, the sky filters in through steel railings, a model of the solar system and two large clocks suspended on bearings, each with moving parts. To accommodate the site’s long and narrow dimensions, Wink designed a walkway that functions as “a sort of experiential tunnel that you move through.” And because the sun casts shadows on the sculptural steel rail throughout the day, she says, the space itself seems to shift and alter, “making it dynamic anytime you experience it.”

Such subtle references to time and space may be less evident to a casual observer, Wink concedes, but it is the experience that matters. “As people walk up the ramp to the train they are in the installation. They are immersed. That’s an important part of my work: how a viewer interacts physically with the sculpture.”

Toward the Physicality of Sculpture

Wink’s early installations—a field of ceramic blades of grass, for example—were temporary exhibitions built to be dismantled. In time, she says, “I’d be packing them up and putting them away and thinking ‘what am I doing this for?’” In response she experimented with biodegradable materials that deteriorate back into the environment. “And then I had an opportunity to design and build “Sanctuary,” a large stone labyrinth earthwork sculpture at Central Michigan University where I was teaching,” she remembers. “It just felt right to build something more permanent.”

Photo credit – Peggy Brisbane

Originally trained in ceramics and other fine art mediums, today Wink’s projects incorporate steel, stone, cement and other landscape materials. Yet handcrafted ceramic tiles remain a constant, she says, not only because they provide a means for narrative but also because such detail “invites the viewer into the sculptural experience on a more intimate scale.” The commemorative piece “Community Quilt, for example, blankets a seating area with colorful tiles created by residents to honor a beloved teacher. The Tree of Knowledge outside Roswell’s Public Library is covered with thousands of “word” tiles made by the artist, her project team and multi-generational residents throughout the city.

“I love the idea of making a massive piece with multiple details,” Wink says. “Visitors to a site may be walking through it when they see a feature that draws them in closer—they stay longer and observe the sky, light, the shadows and space around them.”

To Wink, for whom nature remains the greatest source of inspiration, compelling a visitor to pause and reflect on one’s surroundings may be her greatest objective. “It’s really about both the macro and the micro,” she says of the comprehensive environments she designs. “I am interested in all of the parts, large and small, coming together into a meaningful whole, just like our universe. It’s what we are all a part of.”